The Kleis Manual

“Mathematics is the language with which God has written the universe.” — Galileo Galilei

Welcome to The Kleis Manual, the official guide to the Kleis mathematical specification language.

What is Kleis?

Kleis is a structure-oriented mathematical formalization language with Z3 verification and LAPACK numerics.

Philosophy: Structures — the foundation of everything.

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Grammar | Fully implemented |

| Tests | 1,762 Rust unit tests |

| Examples | 71 Kleis files across 15+ domains |

| Built-in Functions | 100+ (including LAPACK numerical operations) |

Core Capabilities

- 🏗️ Structure-first design — define mathematical objects by their axioms, not just their data

- ✅ Z3 verification — prove properties with SMT solving

- 🔢 LAPACK numerics — eigenvalues, SVD, matrix exponentials, and more

- 📐 Symbolic mathematics — work with expressions, not just numbers

- 🔬 Scientific computing — differential geometry, tensor calculus, control systems

- 🔄 Turing complete — a full programming language, not just notation

Computational Universality: Kleis is Turing complete. This was demonstrated by implementing a complete LISP interpreter in Kleis (see Appendix: LISP Interpreter). The combination of algebraic data types, pattern matching, and recursion enables arbitrary computation.

Domain Coverage

Kleis has been used to formalize:

| Domain | Examples |

|---|---|

| Mathematics | Differential forms, tensor algebra, complex analysis, number theory |

| Physics | Dimensional analysis, quantum entanglement, orbital mechanics |

| Control Systems | LQG controllers, eigenvalue analysis, state-space models |

| Ontology | Projected Ontology Theory, spacetime types |

| Protocols | IPv4 packets, IP routing, stop-and-wait ARQ |

| Authorization | OAuth2 scopes, Google Zanzibar |

| Formal Methods | Petri nets, mutex verification |

| Games | Chess, Contract Bridge, Sudoku |

Who is This For?

Kleis is for anyone who thinks in terms of structures and axioms:

- Mathematicians — formalize theorems, verify properties, explore number theory

- Physicists — tensor algebra, differential geometry, dimensional analysis

- Engineers — control systems, protocol specifications, verified designs

- Security architects — authorization policies (Zanzibar, OAuth2)

- Researchers — formalize new theories with Z3 verification

- Functional programmers — if you enjoy Haskell or ML, you’ll feel at home

If you’ve ever wished you could prove your specifications are consistent, Kleis is for you.

Why Kleis Now?

Modern systems demand formal verification:

| Challenge | How Kleis Helps |

|---|---|

| Security & Compliance | Machine-checkable proofs for audit trails across sectors |

| Complex Systems | Verify rules across IoT, enterprise, and distributed systems |

| AI-Generated Content | Verify AI outputs against formal specifications |

Universal verification — same rigor for mathematics, business rules, and beyond.

How to Read This Guide

Each chapter builds on the previous ones. We start with the basics:

- Starting Out — expressions, operators, basic syntax

- Types — naming and composing structures

- Functions — operations with laws

Then we explore core concepts:

- Algebraic Types — data definitions and constructors

- Pattern Matching — elegant case analysis

- Let Bindings — local definitions

- Quantifiers and Logic — ∀, ∃, and logical operators

- Conditionals — if-then-else

And advanced features:

- Structures — the foundation of everything

- Implements — structure implementations

- Z3 Verification — proving things with SMT

Philosophy: In Kleis, structures define what things are through their operations and axioms. Types are names for structures. A metric tensor isn’t “a 2D array” — it’s “something satisfying metric axioms.”

A Taste of Kleis

Here’s what Kleis looks like:

// Define a function

define square(x) = x * x

// With type annotation

define double(x : ℝ) : ℝ = x + x

// Create a structure with axioms

structure Group(G) {

operation e : G // identity

operation inv : G → G // inverse

operation mul : G × G → G // multiplication

axiom left_identity : ∀ x : G . mul(e, x) = x

axiom left_inverse : ∀ x : G . mul(inv(x), x) = e

}

// Numerical computation

example "eigenvalues" {

let A = Matrix([[1, 2], [3, 4]]) in

out(eigenvalues(A)) // Pretty-printed output

}

Getting Started

Ready? Let’s dive in!

→ Start with Chapter 1: Starting Out

Starting Out

Your First Kleis Expression

The simplest things in Kleis are expressions. An expression is anything that has a value:

define answer = 42 // A number

define pi_approx = 3.14159 // A decimal

define sum(x, y) = x + y // An arithmetic expression

define angle_sin(θ) = sin(θ) // A function call

The REPL

The easiest way to experiment with Kleis is the REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop):

$ cargo run --bin repl

🧮 Kleis REPL v0.1.0

Type :help for commands, :quit to exit

λ> 2 + 2

2 + 2

λ> let x = 5 in x * x

times(5, 5)

Basic Arithmetic

Kleis supports the usual arithmetic operations:

define add_example = 2 + 3 // Addition: 5

define sub_example = 10 - 4 // Subtraction: 6

define mul_example = 3 * 7 // Multiplication: 21

define div_example = 15 / 3 // Division: 5

define pow_example = 2 ^ 10 // Exponentiation: 1024

Variables and Definitions

Use define to create named values:

define pi = 3.14159

define e = 2.71828

define golden_ratio = (1 + sqrt(5)) / 2

Functions are defined similarly:

define square(x) = x * x

define cube(x) = x * x * x

define area_circle(r) = pi * r^2

Comments

Kleis uses C-style comments:

// This is a single-line comment

define x = 42 // Inline comment

/*

Multi-line comments

use slash-star syntax

*/

Unicode Support

Kleis embraces mathematical notation with full Unicode support:

// Greek letters

define α = 0.5

define β = 1.0

define θ = π / 4

// Mathematical symbols in axioms

axiom reflexivity : ∀(x : ℝ). x = x // Universal quantifier

axiom positive_exists : ∃(y : ℝ). y > 0 // Existential quantifier

You can use ASCII alternatives too:

| Unicode | ASCII Alternative |

|---|---|

∀ | forall |

∃ | exists |

→ | -> |

What’s Next?

Now that you can write basic expressions, let’s learn about the type system!

Types and Values

Why Types Matter

Types are the foundation of Kleis. Every expression has a type, and the type system catches errors before they become problems.

define answer = 42 // 42 is an integer

define pi_val = 3.14 // 3.14 is a real number

define flag = True // True is a boolean

Built-in Types

Numeric Types

| Type | Unicode | Full Name | ASCII | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | ℕ | Nat | N | 0, 42, 100 |

| Integer | ℤ | Int | Z | -5, 0, 17 |

| Rational | ℚ | Rational | Q | rational(1, 2), rational(3, 4) |

| Real | ℝ | Real or Scalar | R | 3.14, -2.5, √2 |

| Complex | ℂ | Complex | C | 3 + 4i, i |

Other Basic Types

| Type | Unicode | Full Name | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boolean | 𝔹 | Bool | True, False |

| String | — | String | "hello", "world" |

| Unit | — | Unit | () |

Parameterized Primitive Types

| Type | Syntax | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Bit-Vector | BitVec(n) | n-bit binary vector (e.g., BitVec(8), BitVec(32)) |

| Set | Set(T) | Set of elements of type T (e.g., Set(ℤ), Set(ℝ)) |

// Boolean values

define flag = True

define not_flag = False

// Boolean in quantified expressions (inside structures)

structure BoolExamples {

axiom reflexive_unicode : ∀(p : 𝔹). p = p

axiom reflexive_full : ∀(q : Bool). q = q

}

The Unit Type

The Unit type represents “no meaningful value” — like void in C or () in Rust/Haskell. It has exactly one value: ().

When to use Unit:

- Result types that can fail but return nothing on success:

// A validation that succeeds with () or fails with an error message

data ValidationResult = Ok(Unit) | Err(String)

define validate_positive(x : ℝ) : ValidationResult =

if x > 0 then Ok(()) else Err("must be positive")

- Optional values where presence matters, not content:

// Option type - Some(value) or None

data Option(T) = Some(T) | None

// A flag that's either set or not (no associated value)

define flag_set : Option(Unit) = Some(())

define flag_unset : Option(Unit) = None

- Proof terms with no computational content:

// A theorem that x = x (the proof itself carries no data)

structure Reflexivity {

axiom refl : ∀(x : ℝ). x = x

}

// The "witness" of this axiom would have type Unit

Type Annotations

You can explicitly annotate types with ::

// Variable annotation

define typed_let = let x : ℝ = 3.14 in x * 2

// Function parameter and return types

define f(x : ℝ) : ℝ = x * x

// Expression-level annotation (ascription)

define sum_typed(a, b) = (a + b) : ℝ

Type Aliases

Type aliases give a new name to an existing type, making your code more readable and self-documenting.

The type Keyword

type Probability = ℝ

type Temperature = ℝ

type Velocity = ℝ

Now you can use Probability instead of ℝ to make your intent clear:

define coin_flip : Probability = 0.5

define boiling_point : Temperature = 100.0

Why Use Type Aliases?

- Readability —

Probabilityis clearer thanℝ - Documentation — the type name explains what the value represents

- Refactoring — change the underlying type in one place

Function Type Aliases

Type aliases are especially useful for complex function types:

type RealFunction = ℝ → ℝ

type BinaryOp = ℝ → ℝ → ℝ

type Predicate = ℝ → Bool

Now instead of writing (ℝ → ℝ) → ℝ, you can write:

type Integrator = RealFunction → ℝ

Parameterized Type Aliases

Type aliases can have parameters:

type Pair(T) = T → T → T

type Endomorphism(T) = T → T

Aliases for Data Types and Structures

Type aliases work with user-defined types too:

// Alias for a data type (sum type)

data Option(T) = Some(value : T) | None

type MaybeInt = Option(ℤ)

type MaybeString = Option(String)

// Alias for a structure (product type)

structure Point {

x : ℝ

y : ℝ

}

type Coordinate = Point

// Alias for nested ADTs

data Result(T, E) = Ok(value : T) | Err(error : E)

type IntResult = Result(ℤ, String)

Note: Type aliases create a synonym —

Probabilityandℝare interchangeable. They don’t create a distinct new type.

Function Types

Functions have types too! The notation A → B means “a function from A to B”:

// square takes a Real and returns a Real

define square(x : ℝ) : ℝ = x * x

// Type: ℝ → ℝ

// add takes two Reals and returns a Real

define add(x : ℝ, y : ℝ) : ℝ = x + y

// Type: ℝ × ℝ → ℝ (or equivalently: ℝ → ℝ → ℝ)

Higher-Order Function Types

Functions can take other functions as arguments or return functions. These are called higher-order functions:

// A function that takes a function as an argument

define apply_twice(f : ℝ → ℝ, x : ℝ) : ℝ = f(f(x))

// Type: (ℝ → ℝ) × ℝ → ℝ

// A function that returns a function

define make_adder(n : ℝ) : ℝ → ℝ = ???

// Type: ℝ → (ℝ → ℝ)

The parentheses matter! Compare:

(ℝ → ℝ) → ℝ— takes a function, returns a numberℝ → (ℝ → ℝ)— takes a number, returns a functionℝ → ℝ → ℝ— curried function (associates right:ℝ → (ℝ → ℝ))

Function Type Examples

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

ℝ → ℝ | Function from real to real |

ℝ → ℝ → ℝ | Curried binary function |

(ℝ → ℝ) → ℝ | Takes a function, returns a value (e.g., definite integral) |

ℝ → (ℝ → ℝ) | Returns a function (function factory) |

(ℝ → ℝ) → (ℝ → ℝ) | Function transformer (e.g., derivative operator) |

Set Types

Kleis provides a built-in Set(T) type backed by Z3’s native set theory. Sets are unordered collections of unique elements:

// Declare a set type

define S : Set(ℤ)

// Set operations (see stdlib/sets.kleis for full structure)

in_set(x, S) // Membership: x ∈ S → Bool

union(A, B) // Union: A ∪ B → Set(T)

intersect(A, B) // Intersection: A ∩ B → Set(T)

difference(A, B) // Difference: A \ B → Set(T)

complement(A) // Complement: ᶜA → Set(T)

subset(A, B) // Subset test: A ⊆ B → Bool

insert(x, S) // Add element: S ∪ {x} → Set(T)

remove(x, S) // Remove element: S \ {x} → Set(T)

singleton(x) // Singleton set: {x} → Set(T)

empty_set // Empty set: ∅

Set Theory Axioms

Sets come with a complete axiomatization (see stdlib/sets.kleis):

structure SetTheory(T) {

// Core operations

operation in_set : T → Set(T) → Bool

operation union : Set(T) → Set(T) → Set(T)

operation intersect : Set(T) → Set(T) → Set(T)

element empty_set : Set(T)

// Extensionality: sets are equal iff they have the same elements

axiom extensionality: ∀(A B : Set(T)).

(∀(x : T). in_set(x, A) ↔ in_set(x, B)) → A = B

// Union definition

axiom union_def: ∀(A B : Set(T), x : T).

in_set(x, union(A, B)) ↔ (in_set(x, A) ∨ in_set(x, B))

// De Morgan's laws

axiom de_morgan_union: ∀(A B : Set(T)).

complement(union(A, B)) = intersect(complement(A), complement(B))

}

Using Sets in Verification

Sets are particularly useful for specifying properties involving collections:

structure MetricSpace(X) {

operation d : X → X → ℝ

operation ball : X → ℝ → Set(X)

// Open ball definition

axiom ball_def: ∀(center : X, radius : ℝ, x : X).

in_set(x, ball(center, radius)) ↔ d(x, center) < radius

}

Parametric Types

Types can have parameters:

// Parametric type examples:

List(ℤ) // List of integers

Matrix(3, 3, ℝ) // 3×3 matrix of reals

Vector(4) // 4-dimensional vector

Set(ℝ) // Set of real numbers

Dimension Expressions

When working with parameterized types like Matrix(m, n, ℝ), the dimension parameters are not just simple numbers — they can be dimension expressions. This enables type-safe operations where dimensions depend on each other.

Supported Dimension Expressions

| Category | Operators | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic | +, -, *, / | n+1, 2*n, n/2 |

| Power | ^ | n^2, 2^k |

| Grouping | ( ) | (n+1)*2 |

| Functions | min, max | min(m, n) |

Why Dimension Expressions Matter

Consider the realification functor from control theory, which embeds a complex n×n matrix into a real 2n×2n matrix:

// Complex matrix represented as (real_part, imag_part)

type ComplexMatrix(m: Nat, n: Nat) = (Matrix(m, n, ℝ), Matrix(m, n, ℝ))

// Realification: embed C^(n×n) into R^(2n×2n)

structure Realification(n: Nat) {

operation realify : ComplexMatrix(n, n) → Matrix(2*n, 2*n, ℝ)

operation complexify : Matrix(2*n, 2*n, ℝ) → ComplexMatrix(n, n)

}

The 2*n dimension expression captures the invariant that the output dimension is always twice the input dimension.

How Dimension Unification Works

When Kleis type-checks your code, it must verify that dimension expressions match. This uses a built-in dimension solver that can handle common arithmetic constraints.

What the Solver Can Unify

| Expression 1 | Expression 2 | Result |

|---|---|---|

2*n | 2*n | ✅ Structurally equal |

2*n | 6 | ✅ Solved: n = 3 |

n + 1 | 5 | ✅ Solved: n = 4 |

n^2 | 9 | ✅ Solved: n = 3 |

2^k | 8 | ✅ Solved: k = 3 |

What the Solver Rejects

| Expression 1 | Expression 2 | Result |

|---|---|---|

2*n | n | ❌ Different structure (unless n = 0) |

n + 1 | n | ❌ Different structure |

n*m | 6 | ⚠️ Underdetermined |

Examples in Practice

Matrix multiplication requires matching inner dimensions:

// Matrix(m, n) × Matrix(n, p) → Matrix(m, p)

structure MatrixMultiply(m: Nat, n: Nat, p: Nat) {

operation matmul : Matrix(m, n, ℝ) → Matrix(n, p, ℝ) → Matrix(m, p, ℝ)

}

The n dimension must match on both sides — the solver verifies this.

SVD decomposition produces matrices with min(m, n) dimensions:

// Illustrative — tuple return types in structures are aspirational

structure SVD(m: Nat, n: Nat) {

// A = U * Σ * Vᵀ where Σ is min(m,n) × min(m,n)

operation svd : Matrix(m, n, ℝ) →

(Matrix(m, min(m,n), ℝ), Matrix(min(m,n), min(m,n), ℝ), Matrix(min(m,n), n, ℝ))

}

Simplification

The dimension solver simplifies expressions before comparing them:

| Expression | Simplified |

|---|---|

0 + n | n |

1 * n | n |

n^1 | n |

n^0 | 1 |

2 * 3 | 6 |

This means Matrix(1*n, n+0, ℝ) correctly unifies with Matrix(n, n, ℝ).

Design Philosophy

The dimension solver is deliberately bounded:

- It handles practical cases (linear arithmetic, powers, min/max)

- It fails clearly on complex constraints it cannot solve

- It doesn’t require external dependencies (no SMT solver needed for type checking)

If you need more advanced constraint solving, use the :verify command with Z3 at the value level.

Type Inference

Kleis often infers types automatically:

define double(x) = x + x

// Kleis infers: double : ℝ → ℝ (or more general)

define square_five = let y = 5 in y * y

// Kleis infers: y : ℤ

But explicit types make code clearer and catch errors earlier!

The Type Hierarchy

Any

/ | \ \

Scalar String Collection Set(T)

/ \ |

ℂ Bool List

| / \

ℝ Vector Matrix

|

ℚ

|

ℤ

|

ℕ

Note: ℕ ⊂ ℤ ⊂ ℚ ⊂ ℝ ⊂ ℂ (naturals ⊂ integers ⊂ rationals ⊂ reals ⊂ complex)

Set(T) is parameterized by its element type. Set(ℤ) is a set of integers, Set(ℝ) is a set of reals, etc.

Type Promotion (Embedding)

When you mix numeric types in an expression, Kleis automatically promotes the smaller type to the larger one. This is called type embedding, not subtyping.

Embedding vs Subtyping

| Concept | Meaning | Kleis Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Subtyping | S can be used anywhere T is expected, with identical behavior | Not used |

| Embedding | S can be converted to T via an explicit lift function | ✓ Used |

The difference is subtle but important:

// Embedding: Integer 3 is lifted to Rational before the operation

rational(1, 2) + 3

// Becomes: rational_add(rational(1, 2), lift(3))

// Result: rational(7, 2) — exact!

How Promotion Works

- Type inference determines the result type (the “common supertype”)

- Lifting converts arguments to the target type

- Operation executes at the target type

Int + Rational

↓ find common supertype

Rational

↓ lift Int to Rational

lift(Int) + Rational

↓ execute operation

rational_add(Rational, Rational)

↓

Rational result

The Promotes Structure

Type promotion is defined by the Promotes(From, To) structure:

structure Promotes(From, To) {

operation lift : From → To

}

// Built-in promotions

implements Promotes(ℕ, ℤ) { operation lift = builtin_nat_to_int }

implements Promotes(ℤ, ℚ) { operation lift = builtin_int_to_rational }

implements Promotes(ℚ, ℝ) { operation lift = builtin_rational_to_real }

implements Promotes(ℝ, ℂ) { operation lift = builtin_real_to_complex }

Defining Your Own Promotions

You can define promotions for your own types. Unlike built-in types (which use builtin_* functions), you must write the conversion function yourself:

data Percentage = Pct(value: ℝ)

// Step 1: Define the conversion function

define pct_to_real(p: Percentage) : ℝ =

match p { Pct(v) => divide(v, 100) }

// Step 2: Register the promotion, referencing YOUR function

implements Promotes(Percentage, ℝ) {

operation lift = pct_to_real // References the function above

}

Now this works in the REPL:

λ> :eval 0.5 + pct_to_real(Pct(25))

✅ 0.75

Key difference from built-in types:

| Type | Lift Implementation |

|---|---|

Built-in (ℤ → ℚ) | operation lift = builtin_int_to_rational (provided by Kleis) |

| User-defined | operation lift = your_function (you must define it) |

Important: For concrete execution (

:eval), you must provide an actualdefinefor the lift function. Without it:

:verify(symbolic) — Works (Z3 treatsliftas uninterpreted):eval(concrete) — Fails (“function not found”)

Precision Considerations

Warning: Promotion can lose precision!

| Promotion | Precision |

|---|---|

ℕ → ℤ | ✓ Exact (integers contain all naturals) |

ℤ → ℚ | ✓ Exact (rationals contain all integers) |

ℚ → ℝ | ⚠️ May lose precision (floating-point approximation) |

ℝ → ℂ | ✓ Exact (complex with zero imaginary part) |

// Exact in Rational

define third : ℚ = rational(1, 3) // Exactly 1/3

// Approximate in Real (floating-point)

define approx : ℝ = 1.0 / 3.0 // 0.333333...

// If you promote:

define promoted = third + 0.5 // third lifted to ℝ, loses exactness!

Recommendation: When precision matters, be explicit about types:

// Keep it in Rational for exact arithmetic

define exact_sum : ℚ = rational(1, 3) + rational(1, 6) // Exactly 1/2

// Or use type annotations to prevent accidental promotion

define result(x : ℚ, y : ℚ) : ℚ = x + y

No LSP Violations

Because Kleis uses embedding (not subtyping), operations are always resolved at the target type after lifting. This means:

Int + Intuses integer additionInt + Rationallifts the Int first, then uses rational addition- You never accidentally get integer truncation when you expected rational division

5 / 3 // Integer division → 1 (if both are Int)

rational(5, 1) / rational(3, 1) // Rational division → 5/3 (exact)

What’s Next?

Types are the foundation. Now let’s see how to define functions!

Functions

Defining Functions

Functions are defined with define:

define square(x) = x * x

define cube(x) = x * x * x

define add(x, y) = x + y

Functions with Type Annotations

For clarity and safety, add type annotations:

define square(x : ℝ) : ℝ = x * x

define distance(x : ℝ, y : ℝ) : ℝ = sqrt(x^2 + y^2)

define normalize(v : Vector(3)) : Vector(3) = v / magnitude(v)

Multi-Parameter Functions

Functions can take multiple parameters:

define add(x, y) = x + y

define volume_box(l, w, h) = l * w * h

define dot_product(a, b, c, x, y, z) = a*x + b*y + c*z

Recursive Functions

Functions can call themselves:

define factorial(n : ℕ) : ℕ =

if n = 0 then 1

else n * factorial(n - 1)

define fibonacci(n : ℕ) : ℕ =

if n ≤ 1 then n

else fibonacci(n-1) + fibonacci(n-2)

Built-in Mathematical Functions

Kleis includes standard mathematical functions:

Trigonometric

sin(x) cos(x) tan(x)

asin(x) acos(x) atan(x)

sinh(x) cosh(x) tanh(x)

Exponential and Logarithmic

exp(x) // e^x

ln(x) // natural log

log(x) // base-10 log

log(b, x) // log base b of x

Other

sqrt(x) // square root

abs(x) // absolute value

floor(x) // round down

ceil(x) // round up

min(x, y) // minimum

max(x, y) // maximum

Lambda Expressions (Anonymous Functions)

Lambda expressions allow you to create anonymous functions inline:

define square_lambda = λ x . x * x

define increment = lambda x . x + 1

define add_lambda = λ x . λ y . x + y

define square_typed = λ (x : ℝ) . x^2

define curried_add = λ x . λ y . x + y

Lambda expressions are first-class values - you can pass them to functions:

// Pass lambda to higher-order function

define doubled_list = map(λ x . x * 2, [1, 2, 3])

// Or define inline

define result = apply(λ x . x + 1, 5)

Higher-Order Functions

Functions can take functions as arguments:

// Apply a function twice

define apply_twice(f, x) = f(f(x))

// Example usage:

define inc(x) = x + 1

define result = apply_twice(inc, 5) // Result: 7

Partial Application and Currying

With lambda expressions, you can create curried functions:

// Curried addition

define add = λ x . λ y . x + y

// Partial application creates specialized functions

define add5 = add(5) // λ y . 5 + y

define eight = add5(3) // Result: 8

Named Arguments (v0.96)

For plotting and numeric functions, Kleis supports named arguments (keyword arguments):

// Named arguments come after positional arguments

diagram(

bar(xs, ys, offset = -0.2, width = 0.4, label = "Data"),

plot(x, y, color = "blue", yerr = errors),

width = 10,

height = 7,

title = "My Chart"

)

Syntax

Named arguments use = (not ==) and must come after all positional arguments:

// ✅ Valid: positional first, then named

f(a, b, x = 1, y = 2)

// ✅ Valid: all named

f(x = 1, y = 2)

// ❌ Invalid: positional after named

f(x = 1, a, b) // Error!

Parser Transformation

Named arguments are syntactic sugar. The parser transforms them into a record expression:

// You write:

bar(xs, ys, offset = -0.2, width = 0.4)

// Parser produces:

bar(xs, ys, record(

field("offset", -0.2),

field("width", 0.4)

))

Limitations: Numeric Only

Important: Named arguments are designed for concrete numeric computation (plotting, configuration). They cannot be used in:

structuredefinitionsaxiomdeclarationsimplementsblocks- Z3 verification proofs

// ❌ Does NOT work in axioms

structure Bad {

axiom wrong: f(x = 1) // ERROR: named args not for axioms

}

// ✅ Works in plotting/computation

let xs = [0, 1, 2, 3]

let ys = [10, 20, 15, 25]

diagram(bar(xs, ys, color = "blue"))

Why This Design?

Named arguments are opaque to the type system:

- Type inference sees

recordas an opaque type - Unification doesn’t look inside records

- Z3 never receives record expressions

- Built-in functions consume records at runtime

This ensures named arguments don’t interfere with symbolic mathematics while providing convenient syntax for plotting and configuration.

What’s Next?

Learn about algebraic data types for structured data!

Algebraic Data Types

What Are ADTs?

Algebraic Data Types (ADTs) let you define custom data structures by combining simpler types. There are two main kinds:

- Product types — “this AND that” (records, tuples)

- Sum types — “this OR that” (variants, enums)

Product Types

A product type combines multiple values:

// A point has an x AND a y

structure Point {

x : ℝ

y : ℝ

}

// A person has a name AND an age

structure Person {

name : String

age : ℕ

}

Sum Types (Variants)

A sum type represents alternatives — a value that can be one of several different forms.

The data Keyword

In Kleis, you define sum types using the data keyword:

data TypeName = Constructor1 | Constructor2 | Constructor3

Syntax breakdown:

data— keyword that introduces a new type definitionTypeName— the name of your new type (starts with uppercase)=— separates the type name from its constructorsConstructor1,Constructor2, etc. — the possible variants (each starts with uppercase)|— read as “or” — separates the alternatives

Constructors with Data

Constructors can carry data (fields):

data TypeName = Constructor1(field1 : Type1) | Constructor2(field2 : Type2, field3 : Type3)

Each constructor acts like a function that creates a value of the type.

Parameterized Types (Generics)

Types can have parameters, making them work with any type:

data Option(T) = Some(value : T) | None

Here T is a type parameter. You can use Option(ℕ) for optional natural numbers, Option(String) for optional strings, etc. The type is generic — it works for any T.

Examples

// A shape is a Circle OR a Rectangle OR a Triangle

data Shape = Circle(radius : ℝ) | Rectangle(width : ℝ, height : ℝ) | Triangle(a : ℝ, b : ℝ, c : ℝ)

// An optional value is Some(value) OR None

data Option(T) = Some(value : T) | None

// A result is Ok(value) OR Err(message)

data Result(T, E) = Ok(value : T) | Err(error : E)

Pattern Matching with ADTs

ADTs shine with pattern matching:

define area(shape) =

match shape {

Circle(r) => π * r^2

Rectangle(w, h) => w * h

Triangle(a, b, c) =>

let s = (a + b + c) / 2 in

sqrt(s * (s-a) * (s-b) * (s-c))

}

Recursive Types

Types can refer to themselves:

// A list is either empty (Nil) or a value followed by another list (Cons)

data List(T) {

Nil

Cons(head : T, tail : List(T))

}

// A binary tree

data Tree(T) {

Leaf(value : T)

Node(left : Tree(T), value : T, right : Tree(T))

}

The Mathematical Perspective

Why “algebraic”?

- Product types correspond to multiplication:

Point = ℝ × ℝ - Sum types correspond to addition:

Option(T) = T + 1

The number of possible values follows algebra:

Boolhas 2 valuesBool × Boolhas 2 × 2 = 4 valuesBool + Boolhas 2 + 2 = 4 values

Practical Example: Expression Trees

ADTs are perfect for representing mathematical expressions:

data Expression =

ENumber(value : ℝ)

| EVariable(name : String)

| EOperation(name : String, args : List(Expression))

// Helper constructors for cleaner syntax

define num(n) = ENumber(n)

define var(x) = EVariable(x)

define e_add(a, b) = EOperation("plus", Cons(a, Cons(b, Nil)))

define e_mul(a, b) = EOperation("times", Cons(a, Cons(b, Nil)))

define e_neg(a) = EOperation("neg", Cons(a, Nil))

define eval_expr(expr, env) =

match expr {

ENumber(v) => v

EVariable(name) => lookup(env, name)

EOperation("plus", Cons(l, Cons(r, Nil))) =>

eval_expr(l, env) + eval_expr(r, env)

EOperation("times", Cons(l, Cons(r, Nil))) =>

eval_expr(l, env) * eval_expr(r, env)

EOperation("neg", Cons(e, Nil)) =>

-eval_expr(e, env)

_ => 0

}

What’s Next?

Let’s dive deeper into pattern matching!

Pattern Matching

The Power of Match

Pattern matching is one of Kleis’s most powerful features. It lets you destructure data and handle different cases elegantly:

define describe(n) =

match n {

0 => 0

1 => 1

_ => 2

}

Basic Patterns

Literal Patterns

Match exact values:

define describe_literal(x) =

match x {

0 => "zero"

1 => "one"

42 => "the answer"

_ => "something else"

}

Variable Patterns

Bind matched values to names:

define sum_point(point) =

match point {

Point(x, y) => x + y

}

Wildcard Pattern

The underscore _ matches anything:

define describe_pair(pair) =

match pair {

(_, 0) => "second is zero"

(0, _) => "first is zero"

_ => "neither is zero"

}

Nested Patterns

Patterns can be nested arbitrarily:

define sum_tree(tree) =

match tree {

Leaf(v) => v

Node(Leaf(l), v, Leaf(r)) => l + v + r

Node(left, v, right) => v + sum_tree(left) + sum_tree(right)

}

Guards

Add conditions to patterns with if:

define sign(n) =

match n {

x if x < 0 => "negative"

x if x > 0 => "positive"

_ => "zero"

}

As-Patterns

Bind the whole match while also destructuring:

define filter_head(list) =

match list {

Cons(h, t) as whole =>

if h > 10 then whole

else t

Nil => Nil

}

Pattern Matching in Let

Destructure directly in let bindings:

define distance_squared(origin) =

let Point(x, y) = origin in x^2 + y^2

define sum_first_two(triple) =

let (first, second, _) = triple in first + second

Pattern Matching in Function Parameters

With lambda expressions now available, you can combine them with match:

// Pattern matching with lambdas

define fst = λ pair . match pair { (a, _) => a }

define snd = λ pair . match pair { (_, b) => b }

Alternative workaround:

define fst(pair) =

match pair {

(a, _) => a

}

Exhaustiveness

Kleis checks that your patterns cover all cases:

// ⚠️ Warning: non-exhaustive patterns

define incomplete(opt) =

match opt {

Some(x) => x

}

// ✓ Complete

define complete(opt) =

match opt {

Some(x) => x

None => 0

}

Real-World Example: Symbolic Differentiation

Pattern matching makes symbolic math elegant:

define diff(expr, var) =

match expr {

Const(_) => Const(0)

Var(name) =>

if name = var then Const(1)

else Const(0)

Add(f, g) =>

Add(diff(f, var), diff(g, var))

Mul(f, g) =>

Add(Mul(diff(f, var), g),

Mul(f, diff(g, var)))

Neg(f) =>

Neg(diff(f, var))

}

Note: This

difffunction computes derivatives by pattern matching on expression trees. Kleis also providesD(f, x)andDt(f, x)operations instdlib/calculus.kleisfor verifying derivative properties with Z3. See Applications: Symbolic Differentiation for a detailed comparison.

What’s Next?

Learn about let bindings for local definitions!

Let Bindings

Introduction

Let bindings introduce local variables with limited scope. They’re essential for breaking complex expressions into readable parts.

define square_five = let x = 5 in x * x

// Result: 25

Basic Syntax

let <name> = <value> in <body>

The variable name is only visible within body:

define circle_area = let radius = 10 in π * radius^2

// Result: 314.159...

// 'radius' is not visible outside the let binding

With Type Annotations

Add explicit types for clarity:

define typed_example1 = let x : ℝ = 3.14 in x * 2

define typed_example2 = let n : ℕ = 42 in factorial(n)

define typed_example3 = let v : Vector(3) = [1, 2, 3] in magnitude(v)

Nested Let Bindings

Chain multiple bindings:

define nested_example =

let x = 5 in

let y = 3 in

let z = x + y in

x * y * z

// Result: 5 * 3 * 8 = 120

Shadowing

Inner bindings can shadow outer ones:

define shadowing_example =

let x = 1 in

let x = x + 1 in

let x = x * 2 in

x

// Result: 4 (not 1!)

Each let creates a new scope where x is rebound.

Pure Substitution Semantics

In Kleis, let x = e in body is equivalent to substituting e for x in body:

define substitution_demo = let x = 5 in x + x

// is the same as:

define substitution_result = 5 + 5

This is pure functional semantics — no mutation, no side effects.

Practical Examples

Quadratic Formula

define quadratic_roots(a, b, c) =

let discriminant = b^2 - 4*a*c in

let sqrt_d = sqrt(discriminant) in

let denom = 2 * a in

((-b + sqrt_d) / denom, (-b - sqrt_d) / denom)

Heron’s Formula

define triangle_area(a, b, c) =

let s = (a + b + c) / 2 in

sqrt(s * (s - a) * (s - b) * (s - c))

Complex Calculations

define schwarzschild_metric(r, M) =

let rs = 2 * G * M / c^2 in

let factor = 1 - rs / r in

-c^2 * factor

Let vs Define

define | let ... in |

|---|---|

| Top-level, global | Local scope only |

| Named function/constant | Temporary binding |

| Visible everywhere | Visible only in body |

// Global constant

define pi = 3.14159

// Local temporary in a function

define circumference(radius) = let two_pi = 2 * pi in two_pi * radius

What’s Next?

Learn about quantifiers and logic!

Quantifiers and Logic

Universal Quantifier (∀)

The universal quantifier expresses “for all”:

// Quantified propositions (used inside axioms)

axiom reflexivity : ∀(x : ℝ). x = x

axiom additive_identity : ∀(x : ℝ). x + 0 = x

axiom commutative : ∀(x : ℝ)(y : ℝ). x + y = y + x

ASCII alternative: forall x . ...

Existential Quantifier (∃)

The existential quantifier expresses “there exists”:

// Existential quantifiers

axiom positive_exists : ∃(x : ℝ). x > 0

axiom sqrt2_exists : ∃(y : ℝ). y * y = 2

axiom distinct_exists : ∃(x : ℝ)(y : ℝ). x ≠ y

ASCII alternative: exists x . ...

Combining Quantifiers

Build complex statements:

// Every number has a successor

axiom successor : ∀(n : ℕ). ∃(m : ℕ). m = n + 1

// Density of rationals: between any two reals is a rational

axiom density : ∀(x : ℝ)(y : ℝ). x < y → ∃(q : ℚ). x < q ∧ q < y

Logical Connectives

Conjunction (∧ / and)

define in_range(x) = x > 0 ∧ x < 10 // x is between 0 and 10

define false_example = True ∧ False // False

Disjunction (∨ / or)

define is_binary(x) = x = 0 ∨ x = 1 // x is 0 or 1

define true_example = True ∨ False // True

Implication (→ / implies)

define positive_square(x) = x > 0 → x * x > 0 // If positive, square is positive

define implication(P, Q) = P → Q // If P then Q

Negation (¬ / not)

define nonzero(x) = ¬(x = 0) // x is not zero

define not_true = ¬True // False

Biconditional (↔ / iff)

define zero_iff_square_zero(x) = x = 0 ↔ x * x = 0 // x is zero iff x² is zero

Type Constraints in Quantifiers

Restrict the domain:

axiom naturals_nonneg : ∀(x : ℕ). x ≥ 0

axiom det_inverse : ∀(M : Matrix(n, n)). det(M * M⁻¹) = 1

The where Clause

Add conditions to quantified variables using the where keyword:

structure Field(F) {

element zero : F

element one : F

operation inverse : F → F

// Multiplicative inverse only for non-zero elements

axiom multiplicative_inverse:

∀(x : F) where x ≠ zero. inverse(x) * x = one

}

The where clause restricts the domain before the quantified body is evaluated. This is essential for axioms that don’t apply universally.

More examples:

structure Analysis {

// Division only defined for non-zero denominator

axiom division: ∀(a : ℝ)(b : ℝ) where b ≠ 0. a / b * b = a

// Logarithm only for positive numbers

axiom log_exp: ∀(x : ℝ) where x > 0. exp(log(x)) = x

}

Using Quantifiers in Axioms

Quantifiers are essential in structure axioms:

structure Group(G) {

e : G // Identity element

operation mul : G × G → G

operation inv : G → G

axiom identity : ∀(x : G). mul(e, x) = x ∧ mul(x, e) = x

axiom inverse : ∀(x : G). mul(x, inv(x)) = e

axiom associative : ∀(x : G)(y : G)(z : G).

mul(mul(x, y), z) = mul(x, mul(y, z))

}

Nested Quantifiers (Grammar v0.9)

Quantifiers can appear inside logical expressions:

structure Analysis {

// Quantifier inside conjunction

axiom bounded_positive: (x > 0) ∧ (∀(y : ℝ). abs(y) <= x)

// Quantifier inside implication

axiom dense_rationals: ∀(a b : ℝ). a < b → (∃(q : ℚ). a < q ∧ q < b)

// Deeply nested quantifiers

axiom limit_def: ∀(L : ℝ, ε : ℝ). ε > 0 →

(∃(δ : ℝ). δ > 0 ∧ (∀(x : ℝ). abs(x) < δ → abs(f(x) - L) < ε))

}

Epsilon-Delta Limit Definition

The classic analysis definition now parses correctly:

structure Limits {

axiom epsilon_delta: ∀(f : ℝ → ℝ, L a : ℝ).

has_limit(f, a, L) ↔

(∀(ε : ℝ). ε > 0 → (∃(δ : ℝ). δ > 0 ∧

(∀(x : ℝ). abs(x - a) < δ → abs(f(x) - L) < ε)))

}

Function Types in Quantifiers (Grammar v0.9)

Quantify over functions using the arrow type:

structure FunctionProperties {

// Quantify over a function ℝ → ℝ

axiom continuous: ∀(f : ℝ → ℝ, x : ℝ).

is_continuous(f, x)

// Quantify over multiple functions

axiom composition: ∀(f : ℝ → ℝ, g : ℝ → ℝ).

compose(f, g) = λ x . f(g(x))

// Higher-order function types

axiom curried: ∀(f : ℝ → ℝ → ℝ, a b : ℝ).

f = f

}

Topology with Function Types

structure Topology {

axiom continuity: ∀(f : X → Y, V : Set(Y)).

is_open(V) → is_open(preimage(f, V))

axiom homeomorphism: ∀(f : X → Y, g : Y → X).

(∀(x : X). g(f(x)) = x) ∧ (∀(y : Y). f(g(y)) = y) →

bijective(f)

}

Verification with Z3

Kleis uses Z3 to check quantified statements:

// Z3 can verify this is always true:

axiom add_zero : ∀(x : ℝ). x + 0 = x

// Z3 can find a counterexample for this:

axiom all_positive : ∀(x : ℝ). x > 0

// Z3 finds counterexample: x = -1

Truth Tables

| P | Q | P ∧ Q | P ∨ Q | P → Q | ¬P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T | F |

| T | F | F | T | F | F |

| F | T | F | T | T | T |

| F | F | F | F | T | T |

What’s Next?

Learn about conditional expressions!

Conditionals

If-Then-Else

The basic conditional expression:

if condition then value1 else value2

Examples:

define positive_check(x) = if x > 0 then "positive" else "non-positive"

define factorial(n) = if n = 0 then 1 else n * factorial(n - 1)

define abs(x) = if x ≥ 0 then x else -x

Conditionals Are Expressions

In Kleis, if-then-else is an expression that returns a value:

define doubled_abs(x) =

let result = if x > 0 then x else -x in

result * 2

// Both branches must have compatible types!

// if True then 42 else "hello" // ❌ Type error!

Nested Conditionals

define sign(x) =

if x > 0 then 1

else if x < 0 then -1

else 0

define grade(score) =

if score ≥ 90 then "A"

else if score ≥ 80 then "B"

else if score ≥ 70 then "C"

else if score ≥ 60 then "D"

else "F"

Guards vs If-Then-Else

Pattern matching with guards is often cleaner:

// With if-then-else

define classify_if(n) =

if n < 0 then "negative"

else if n = 0 then "zero"

else "positive"

// With pattern matching and guards

define classify_match(n) =

match n {

x if x < 0 => "negative"

0 => "zero"

_ => "positive"

}

Piecewise Functions

Mathematicians love piecewise definitions:

// Absolute value

define abs_fn(x) =

if x ≥ 0 then x else -x

// Heaviside step function

define heaviside(x) =

if x < 0 then 0

else if x = 0 then 0.5

else 1

// Piecewise polynomial

define piecewise_f(x) =

if x < 0 then x^2

else if x < 1 then x

else 2 - x

Boolean Expressions

Conditions can be complex:

define quadrant(x, y) =

if x > 0 ∧ y > 0 then "first quadrant"

else if x < 0 ∧ y > 0 then "second quadrant"

else if x < 0 ∧ y < 0 then "third quadrant"

else if x > 0 ∧ y < 0 then "fourth quadrant"

else "on an axis"

Short-Circuit Evaluation

Kleis uses short-circuit evaluation for ∧ and ∨:

// If x = 0, division is never evaluated

define check_ratio(x, y) =

if x ≠ 0 ∧ y/x > 1 then "big ratio" else "safe"

What’s Next?

Learn about structures for defining mathematical objects!

Structures

What Are Structures?

Structures define mathematical objects with their properties and operations. Think of them as “blueprints” for mathematical concepts.

structure Vector(n : ℕ) {

// Operations this structure supports

operation add : Vector(n) → Vector(n)

operation scale : ℝ → Vector(n)

operation dot : Vector(n) → ℝ

// Properties that must hold

axiom commutative : ∀(u : Vector(n))(v : Vector(n)).

add(u, v) = add(v, u)

}

Structure Syntax

structure Name(parameters) {

// Elements (constants)

element1 : Type1

// Operations (functions)

operation op1 : InputType → OutputType

// Axioms (properties)

axiom property : logical_statement

}

Structure Members

Structures contain three kinds of members:

The operation Keyword

The operation keyword declares a function that the structure provides:

structure Group(G) {

operation mul : G × G → G // Binary operation

operation inv : G → G // Unary operation

}

Operations declare the signature (types), not the implementation. The implementation is provided in an implements block (see Chapter 10).

The element Keyword

The element keyword declares a distinguished constant of the structure:

structure Monoid(M) {

element e : M // Identity element

operation mul : M × M → M

axiom identity : ∀(x : M). mul(e, x) = x

}

structure Field(F) {

element zero : F // Additive identity

element one : F // Multiplicative identity

}

Elements are constants that satisfy the structure’s axioms. You can also write elements without the element keyword:

structure Ring(R) {

zero : R // Same as "element zero : R"

one : R

}

The axiom Keyword

The axiom keyword declares a property that must hold:

structure Group(G) {

element e : M

operation mul : G × G → G

operation inv : G → G

axiom identity : ∀(x : G). mul(e, x) = x ∧ mul(x, e) = x

axiom inverse : ∀(x : G). mul(x, inv(x)) = e

axiom associative : ∀(x : G)(y : G)(z : G). mul(mul(x, y), z) = mul(x, mul(y, z))

}

Axioms are verified by Z3 when you use implements blocks or run kleis verify.

Example: Complex Numbers

structure Complex {

re : ℝ // real part

im : ℝ // imaginary part

operation add : Complex → Complex

operation mul : Complex → Complex

operation conj : Complex // conjugate

operation mag : ℝ // magnitude

axiom add_commutative : ∀(z : Complex)(w : Complex).

add(z, w) = add(w, z)

axiom magnitude_positive : ∀(z : Complex).

mag(z) ≥ 0

axiom conj_involution : ∀(z : Complex).

conj(conj(z)) = z

}

Parametric Structures

Structures can have type parameters:

structure Matrix(m : ℕ, n : ℕ, T) {

operation transpose : Matrix(n, m, T)

operation add : Matrix(m, n, T) → Matrix(m, n, T)

axiom transpose_involution : ∀(A : Matrix(m, n, T)).

transpose(transpose(A)) = A

}

// Square matrices have more operations

structure SquareMatrix(n : ℕ, T) extends Matrix(n, n, T) {

operation det : T

operation trace : T

operation inv : SquareMatrix(n, T)

axiom det_mul : ∀(A : SquareMatrix(n, T))(B : SquareMatrix(n, T)).

det(mul(A, B)) = det(A) * det(B)

}

Nested Structures

Structures can contain other structures. This enables compositional algebra — defining complex structures from simpler parts:

structure Ring(R) {

// A ring has an additive group

structure additive : AbelianGroup(R) {

operation add : R × R → R

operation negate : R → R

zero : R

}

// And a multiplicative monoid

structure multiplicative : Monoid(R) {

operation mul : R × R → R

one : R

}

// With distributivity connecting them

axiom distributive : ∀(x : R)(y : R)(z : R).

mul(x, add(y, z)) = add(mul(x, y), mul(x, z))

}

Nested structures can go arbitrarily deep:

structure VectorSpace(V, F) {

structure vectors : AbelianGroup(V) {

operation add : V × V → V

zero : V

}

structure scalars : Field(F) {

operation add : F × F → F

operation mul : F × F → F

}

operation scale : F × V → V

}

When using Z3 verification, axioms from nested structures are automatically available.

The extends Keyword

Structures can extend other structures:

structure Monoid(M) {

e : M

operation mul : M × M → M

axiom identity : ∀(x : M). mul(e, x) = x ∧ mul(x, e) = x

axiom associative : ∀(x : M)(y : M)(z : M).

mul(mul(x, y), z) = mul(x, mul(y, z))

}

structure Group(G) extends Monoid(G) {

operation inv : G → G

axiom inverse : ∀(x : G). mul(x, inv(x)) = e ∧ mul(inv(x), x) = e

}

structure AbelianGroup(G) extends Group(G) {

axiom commutative : ∀(x : G)(y : G). mul(x, y) = mul(y, x)

}

The over Keyword

Many mathematical structures are defined “over” a base structure. A vector space is defined over a field, a module over a ring:

// Vector space over a field

structure VectorSpace(V) over Field(F) {

operation add : V × V → V

operation scale : F × V → V

axiom scalar_identity : ∀(v : V). scale(1, v) = v

axiom distributive : ∀(a : F)(u : V)(v : V).

scale(a, add(u, v)) = add(scale(a, u), scale(a, v))

}

// Module over a ring (generalization of vector space)

structure Module(M) over Ring(R) {

operation add : M × M → M

operation scale : R × M → M

}

// Algebra over a ring

structure Algebra(A) over Ring(R) {

operation add : A × A → A

operation scale : R × A → A

operation mul : A × A → A

axiom bilinear : ∀(r : R)(a : A)(b : A).

scale(r, mul(a, b)) = mul(scale(r, a), b)

}

When you use over, Kleis automatically makes the base structure’s axioms available for verification. For example, when verifying VectorSpace axioms, Z3 knows that F satisfies all Field axioms.

Differential Geometry Structures

Kleis shines for differential geometry:

structure Manifold(M, dim : ℕ) {

operation tangent : M → TangentSpace(M)

operation metric : M → Tensor(0, 2)

axiom metric_symmetric : ∀(p : M).

metric(p) = transpose(metric(p))

}

structure RiemannianManifold(M, dim : ℕ) extends Manifold(M, dim) {

operation christoffel : M → Tensor(1, 2)

operation riemann : M → Tensor(1, 3)

operation ricci : M → Tensor(0, 2)

operation scalar_curvature : M → ℝ

// R^a_{bcd} + R^a_{cdb} + R^a_{dbc} = 0

axiom first_bianchi : ∀(p : M).

cyclic_sum(riemann(p)) = 0

}

What’s Next?

Learn how to implement structures!

Implements

From Structure to Implementation

A structure declares what operations exist. An implements block provides the actual definitions:

structure Addable(T) {

operation add : T × T → T

}

implements Addable(ℝ) {

operation add(x, y) = x + y

}

implements Addable(ℤ) {

operation add(x, y) = x + y

}

Full Example: Complex Numbers

// Declare the structure

structure Complex {

re : ℝ

im : ℝ

operation add : Complex → Complex

operation mul : Complex → Complex

operation conj : Complex

operation mag : ℝ

}

// Implement the operations

implements Complex {

operation add(z, w) = builtin_complex_add

operation mul(z, w) = builtin_complex_mul

operation conj(z) = builtin_complex_conj

operation mag(z) = sqrt(z.re^2 + z.im^2)

}

Parametric Implementations

Implement structures with type parameters:

structure Stack(T) {

operation push : T → Stack(T)

operation pop : Stack(T)

operation top : T

operation empty : Bool

}

implements Stack(ℤ) {

operation push = builtin_stack_push

operation pop = builtin_stack_pop

operation top = builtin_stack_top

operation empty = builtin_stack_empty

}

Multiple Implementations

The same structure can have multiple implementations:

structure Orderable(T) {

operation compare : T × T → Ordering

}

// Natural ordering

implements Orderable(ℤ) {

operation compare = builtin_int_compare

}

Implementing Extended Structures

When a structure extends another, implement all operations:

structure Monoid(M) {

operation e : M

operation mul : M × M → M

}

structure Group(G) extends Monoid(G) {

operation inv : G → G

}

// Must implement both Monoid and Group operations

implements Group(ℤ) {

operation e = 0

operation mul(x, y) = x + y

operation inv(x) = -x

}

Builtin Operations

Some operations can’t be defined in pure Kleis — they need native code. The builtin_ prefix connects Kleis to underlying implementations:

implements Matrix(m, n, ℝ) {

operation transpose = builtin_transpose

operation add = builtin_matrix_add

operation mul = builtin_matrix_mul

}

How Builtins Work

When Kleis sees builtin_foo, it:

- Looks up

fooin the native runtime - Calls the Rust/C/hardware implementation

- Returns the result to Kleis

This enables:

- Performance: Native BLAS for matrix operations

- Hardware access: GPUs, network cards, sensors

- System calls: File I/O, networking, threading

- FFI: Calling existing libraries

The Vision: Hardware as Structures

Imagine:

structure NetworkInterface(N) {

operation send : Packet → Result(Unit, Error)

operation receive : Unit → Result(Packet, Error)

axiom delivery : ∀(p : Packet).

connected → eventually(delivered(p))

}

implements NetworkInterface(EthernetCard) {

operation send = builtin_eth_send

operation receive = builtin_eth_receive

}

The axioms define the contract. The builtins provide the implementation. Z3 can verify that higher-level protocols satisfy their specifications given the hardware axioms.

This is how Kleis becomes a universal verification platform — not just for math, but for any system with verifiable properties.

Verification of Implementations

Kleis + Z3 can verify that implementations satisfy axioms:

structure Monoid(M) {

e : M

operation mul : M × M → M

axiom identity : ∀(x : M). mul(e, x) = x ∧ mul(x, e) = x

axiom associative : ∀(x : M)(y : M)(z : M).

mul(mul(x, y), z) = mul(x, mul(y, z))

}

implements Monoid(String) {

element e = ""

operation mul = builtin_concat

}

// Kleis can verify:

// 1. concat("", s) = s for all s ✓

// 2. concat(s, "") = s for all s ✓

// 3. concat(concat(a, b), c) = concat(a, concat(b, c)) ✓

What’s Next?

Learn about Z3 verification in depth!

Z3 Verification

What is Z3?

Z3 is a theorem prover from Microsoft Research. Kleis uses Z3 to:

- Verify mathematical statements

- Find counterexamples when statements are false

- Check that implementations satisfy axioms

Basic Verification

Use verify to check a statement:

axiom commutativity : ∀(x : ℝ)(y : ℝ). x + y = y + x

// Z3 verifies: ✓ Valid

axiom zero_annihilates : ∀(x : ℝ). x * 0 = 0

// Z3 verifies: ✓ Valid

axiom all_positive : ∀(x : ℝ). x > 0

// Z3 finds counterexample: x = -1

Verifying Quantified Statements

Z3 handles universal and existential quantifiers:

axiom additive_identity : ∀(x : ℝ). x + 0 = x

// Z3 verifies: ✓ Valid

axiom squares_nonnegative : ∀(x : ℝ). x * x ≥ 0

// Z3 verifies: ✓ Valid (squares are non-negative)

axiom no_real_sqrt_neg1 : ∃(x : ℝ). x * x = -1

// Z3: ✗ Invalid (no real square root of -1)

axiom complex_sqrt_neg1 : ∃(x : ℂ). x * x = -1

// Z3 verifies: ✓ Valid (x = i works)

Checking Axioms

Verify that definitions satisfy axioms:

structure Group(G) {

e : G

operation mul : G × G → G

operation inv : G → G

axiom identity : ∀(x : G). mul(e, x) = x

axiom inverse : ∀(x : G). mul(x, inv(x)) = e

axiom associative : ∀(x : G)(y : G)(z : G).

mul(mul(x, y), z) = mul(x, mul(y, z))

}

// Define integers with addition

implements Group(ℤ) {

element e = 0

operation mul = builtin_add

operation inv = builtin_negate

}

// Kleis verifies each axiom automatically!

Implication Verification

Prove that premises imply conclusions:

// If x > 0 and y > 0, then x + y > 0

axiom sum_positive : ∀(x : ℝ)(y : ℝ). (x > 0 ∧ y > 0) → x + y > 0

// Z3 verifies: ✓ Valid

// Triangle inequality

axiom triangle_ineq : ∀(x : ℝ)(y : ℝ)(a : ℝ)(b : ℝ).

(abs(x) ≤ a ∧ abs(y) ≤ b) → abs(x + y) ≤ a + b

// Z3 verifies: ✓ Valid

Counterexamples

When verification fails, Z3 provides counterexamples:

axiom square_equals_self : ∀(x : ℝ). x^2 = x

// Z3: ✗ Invalid, Counterexample: x = 2 (since 4 ≠ 2)

axiom positive_greater_than_one : ∀(n : ℕ). n > 0 → n > 1

// Z3: ✗ Invalid, Counterexample: n = 1

Timeout and Limits

Complex statements may time out:

// Very complex statement

verify ∀ M : Matrix(100, 100) . det(M * M') ≥ 0

// Result: ⏱ Timeout (statement too complex)

Verifying Nested Quantifiers (Grammar v0.9)

Grammar v0.9 enables nested quantifiers in logical expressions:

structure Analysis {

// Quantifier inside conjunction - Z3 handles this

axiom bounded: (x > 0) ∧ (∀(y : ℝ). y = y)

// Epsilon-delta limit definition

axiom limit_def: ∀(L a : ℝ, ε : ℝ). ε > 0 →

(∃(δ : ℝ). δ > 0 ∧ (∀(x : ℝ). abs(x - a) < δ → abs(f(x) - L) < ε))

}

Function Types in Verification

Quantify over functions and verify their properties:

structure Continuity {

// Z3 treats f as an uninterpreted function ℝ → ℝ

axiom continuous_at: ∀(f : ℝ → ℝ, a : ℝ, ε : ℝ). ε > 0 →

(∃(δ : ℝ). δ > 0 ∧ (∀(x : ℝ). abs(x - a) < δ → abs(f(x) - f(a)) < ε))

}

Note: Z3 treats function-typed variables as uninterpreted functions, allowing reasoning about their properties without knowing their implementation.

What Z3 Can and Cannot Do

Z3 Excels At:

- Linear arithmetic

- Boolean logic

- Array reasoning

- Simple quantifiers

- Algebraic identities

- Nested quantifiers (Grammar v0.9)

- Function-typed variables

Z3 Struggles With:

- Non-linear real arithmetic (undecidable in general)

- Very deep quantifier nesting (may timeout)

- Transcendental functions (sin, cos, exp)

- Infinite structures

- Inductive proofs over recursive data types

Practical Workflow

- Write structure with axioms

- Implement operations

- Kleis auto-verifies axioms are satisfied

- Use

verifyfor additional properties - Examine counterexamples when verification fails

// Step 1: Define structure

structure Ring(R) {

zero : R

one : R

operation add : R × R → R

operation mul : R × R → R

operation neg : R → R

axiom add_assoc : ∀(a : R)(b : R)(c : R).

add(add(a, b), c) = add(a, add(b, c))

}

// Step 2: Implement for integers

implements Ring(ℤ) {

element zero = 0

element one = 1

operation add = builtin_add

operation mul = builtin_mul

operation neg = builtin_negate

}

// Step 3: Auto-verification happens!

// Step 4: Check additional properties

axiom mul_zero : ∀(x : ℤ). mul(x, zero) = zero

// Z3 verifies: ✓ Valid

Solver Abstraction Layer

While this chapter focuses on Z3, Kleis is designed with a solver abstraction layer that can interface with multiple proof backends.

Architecture

User Code (Kleis Expression)

│

SolverBackend Trait

│

┌─────┴──────┬───────────┬──────────────┐

│ │ │ │

Z3Backend CVC5Backend IsabelleBackend CustomBackend

│ │ │ │

└─────┬──────┴───────────┴──────────────┘

│

OperationTranslators

│

ResultConverter

│

User Code (Kleis Expression)

The SolverBackend Trait

The core abstraction is defined in src/solvers/backend.rs:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub trait SolverBackend {

/// Get solver name (e.g., "Z3", "CVC5")

fn name(&self) -> &str;

/// Get solver capabilities (declared upfront, MCP-style)

fn capabilities(&self) -> &SolverCapabilities;

/// Verify an axiom (validity check)

fn verify_axiom(&mut self, axiom: &Expression)

-> Result<VerificationResult, String>;

/// Check if an expression is satisfiable

fn check_satisfiability(&mut self, expr: &Expression)

-> Result<SatisfiabilityResult, String>;

/// Evaluate an expression to a concrete value

fn evaluate(&mut self, expr: &Expression)

-> Result<Expression, String>;

/// Simplify an expression

fn simplify(&mut self, expr: &Expression)

-> Result<Expression, String>;

/// Check if two expressions are equivalent

fn are_equivalent(&mut self, e1: &Expression, e2: &Expression)

-> Result<bool, String>;

// ... additional methods for scope management, assertions, etc.

}

}Key design principle: All public methods work with Kleis Expression, not solver-specific types. Solver internals never escape the abstraction.

MCP-Style Capability Declaration

Solvers declare their capabilities upfront (inspired by Model Context Protocol):

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub struct SolverCapabilities {

pub solver: SolverMetadata, // name, version, type

pub capabilities: Capabilities, // operations, theories, features

}

pub struct Capabilities {

pub theories: HashSet<String>, // "arithmetic", "boolean", etc.

pub operations: HashMap<String, OperationSpec>,

pub features: FeatureFlags, // quantifiers, evaluation, etc.

pub performance: PerformanceHints, // timeout, max axioms

}

}This enables:

- Coverage analysis - Know what operations are natively supported

- Multi-solver comparison - Choose the best solver for a program

- User extensibility - Add translators for missing operations

Verification Results

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

pub enum VerificationResult {

Valid, // Axiom holds for all inputs

Invalid { counterexample: String }, // Found a violation

Unknown, // Timeout or too complex

}

pub enum SatisfiabilityResult {

Satisfiable { example: String }, // Found satisfying assignment

Unsatisfiable, // No solution exists

Unknown,

}

}Why Multiple Backends?

Different proof systems have different strengths:

| Backend | Strength | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Z3 | Fast SMT solving, decidable theories | Arithmetic, quick checks, counterexamples |

| CVC5 | Finite model finding, strings | Bounded verification, string operations |

| Isabelle | Structured proofs, automation | Complex inductive proofs, formalization |

| Coq/Lean | Dependent types, program extraction | Certified programs, mathematical libraries |

Current Implementation

Currently implemented in src/solvers/:

| Component | Status | Description |

|---|---|---|

SolverBackend trait | ✅ Complete | Core abstraction |

SolverCapabilities | ✅ Complete | MCP-style capability declaration |

Z3Backend | ✅ Complete | Full Z3 integration |

ResultConverter | ✅ Complete | Convert solver results to Kleis expressions |

discovery module | ✅ Complete | List available solvers |

| CVC5Backend | 🔮 Future | Alternative SMT solver |

| IsabelleBackend | 🔮 Future | HOL theorem prover |

Solver Discovery

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use kleis::solvers::discovery;

// List all available backends

let solvers = discovery::list_solvers(); // ["Z3"]

// Check if a specific solver is available

if discovery::is_available("Z3") {

let backend = Z3Backend::new()?;

}

}Benefits of Abstraction

- Solver independence - Swap solvers without code changes

- Unified API - Same methods regardless of backend

- Capability-aware - Know what each solver supports before using it

- Extensible - Add custom backends by implementing the trait

- Future-proof - New provers can be integrated without changing Kleis code

This architecture makes Kleis a proof orchestration layer with beautiful notation, not just another proof assistant.

What’s Next?

Try the interactive REPL!

The REPL

What is the REPL?

The REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop) is an interactive environment for experimenting with Kleis:

$ cargo run --bin repl

🧮 Kleis REPL v0.1.0

Type :help for commands, :quit to exit

λ>

Basic Usage

Enter expressions to evaluate them symbolically:

λ> 2 + 2

2 + 2

λ> let x = 5 in x * x

times(5, 5)

λ> sin(π / 2)

sin(divide(π, 2))

Note: The REPL performs symbolic evaluation, not numeric computation. Expressions are simplified symbolically, not calculated to numbers.

Loading Files

The REPL prompt evaluates expressions. For definitions (define, structure, etc.), use :load:

λ> :load examples/protocols/stop_and_wait.kleis

✅ Loaded: 1 files, 5 functions, 0 structures, 0 data types, 0 type aliases

λ> :env

📋 Defined functions:

next_seq (seq) = ...

valid_ack (sent, ack) = ...

sender_next_state (current_seq, ack_received) = ...

receiver_accepts (expected, received) = ...

receiver_next_state (expected, received) = ...

More examples to load:

λ> :load examples/business/order_to_cash.kleis

✅ Loaded: 1 files, 21 functions, 0 structures, 4 data types, 0 type aliases

λ> :load examples/authorization/zanzibar.kleis

✅ Loaded: 1 files, 13 functions, 0 structures, 0 data types, 0 type aliases

The import Keyword

In Kleis source files, use import to include definitions from other files:

import "stdlib/prelude.kleis"

import "stdlib/matrices.kleis"

// Now you can use definitions from those files

define my_matrix = identity(3)

Import syntax:

import "path/to/file.kleis"— includes all definitions from that file

Imports are processed at parse time. Relative paths are resolved from the importing file’s directory.

Common imports:

import "stdlib/prelude.kleis" // Basic types and operations

import "stdlib/matrices.kleis" // Matrix operations

import "stdlib/complex.kleis" // Complex number support

Standard Library Resolution

Imports starting with stdlib/ are handled specially:

KLEIS_ROOTenvironment variable — If set, Kleis looks for$KLEIS_ROOT/stdlib/...first- Project directory — Kleis walks up from the current file looking for a

stdlib/folder - Current working directory — Falls back to

./stdlib/...

Setting KLEIS_ROOT:

# Add to your shell profile (~/.bashrc, ~/.zshrc, etc.)

export KLEIS_ROOT=/path/to/kleis

# Now stdlib imports work from anywhere

kleis run my_project/main.kleis

This is useful when:

- Working on projects outside the Kleis repository

- Running Kleis from arbitrary directories

- Sharing code that uses the standard library

Note: In the REPL, use

:loadinstead ofimport. The:loadcommand loads a file interactively, whileimportis for use inside.kleissource files.

Verification with Z3

Run verifications interactively with :verify:

λ> :verify x + y = y + x

✅ Valid

λ> :verify x > 0

❌ Invalid - Counterexample: x!2 -> 0

Satisfiability with Z3

Use :sat to find solutions (equation solving):

λ> :sat ∃(z : ℂ). z * z = complex(-1, 0)

✅ Satisfiable

Witness: z_re = 0, z_im = -1

λ> :sat ∃(x : ℝ). x * x = 4

✅ Satisfiable

Witness: x = -2

λ> :sat ∃(x : ℝ). x * x = -1

❌ Unsatisfiable (no solution exists)

λ> :sat ∃(x : ℝ)(y : ℝ). x + y = 10 ∧ x - y = 4

✅ Satisfiable

Witness: x = 7, y = 3

:verify vs :sat:

| Command | Question | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

:verify | Is it always true? (∀) | Prove theorems |

:sat | Does a solution exist? (∃) | Solve equations |

Lambda Expressions

Lambda expressions work at the prompt:

λ> λ x . x * 2

λ x . times(x, 2)

λ> λ x y . x + y

λ x y . x + y

Type Inference

Check types with :type:

λ> :type 42

📐 Type: Int

λ> :type 3.14

📐 Type: Scalar

λ> :type sin

📐 Type: α0

Note: Integer literals (

42) type asInt, real literals (3.14) type asScalar. This enables proper type promotion (e.g.,Int + Rational → Rational).

Concrete Evaluation with :eval

The :eval command performs concrete evaluation — it actually computes results, including recursive functions:

λ> :load examples/meta-programming/lisp_parser.kleis

✅ Loaded: 60 functions

λ> :eval run("(+ 2 3)")

VNum(5)

λ> :eval run("(letrec ((fact (lambda (n) (if (<= n 1) 1 (* n (fact (- n 1))))))) (fact 5))")

VNum(120)

:eval vs :sat vs :verify:

| Command | Execution | Handles Recursion | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

:eval | Concrete (Rust) | ✅ Yes | Compute actual values |

:sat | Symbolic (Z3) | ❌ No (may timeout) | Find solutions |

:verify | Symbolic (Z3) | ❌ No (may timeout) | Prove theorems |

Key insight: Z3 cannot symbolically unroll recursive functions over unbounded data types. Use

:evalfor concrete computation,:sat/:verifyfor symbolic reasoning.

This is what makes Kleis Turing complete — the combination of ADTs, pattern matching, recursion, and concrete evaluation enables arbitrary computation. See Appendix: LISP Interpreter for a complete example.

The Verification Gap (Important!)

Users must understand this fundamental limitation.

The three REPL modes operate on different systems:

| Command | Executes On | Axiom Checking |

|---|---|---|

:eval | Rust builtins / pattern matching | ❌ None |

:verify | Z3’s mathematical model | ✅ Symbolic |

:sat | Z3’s mathematical model | ✅ Symbolic |

The gap:

When you run :verify ∀(a b : ℕ). a + b = b + a, Z3 proves this using its built-in integer arithmetic theory.

When you run :eval 2 + 3, Rust’s + operator computes 5.

We never verify that Rust’s + matches Z3’s +.

The Trusted Computing Base:

These components are assumed correct, never verified:

- Rust compiler

- Builtin implementations (

builtin_add,builtin_mul, etc.) - LAPACK (for matrix operations)

- IEEE 754 floating point

What Kleis provides:

| Capability | Provided? |

|---|---|

| Verify mathematical properties symbolically | ✅ Yes |

| Compute concrete results efficiently | ✅ Yes |

| Prove computation matches specification | ❌ No |

Example:

structure AdditiveMonoid(M) {

operation add : M → M → M

axiom add_comm: ∀(a b : M). add(a, b) = add(b, a)

}

implements AdditiveMonoid(ℕ) {

operation add = builtin_add // Rust's + operator

}

:verify add_comm→ Z3 checks its integer model ✅:eval 2 + 3→ Rust’sbuiltin_addruns ✅- Connection between them → Trusted, not verified ⚠️

This is the pragmatic trade-off Kleis makes: trust the implementation, verify the mathematics.

Value Bindings with :let

Use :let to bind values to names that persist across REPL commands:

λ> :let x = 2 + 3

x = 5

λ> :eval x * 2

✅ 10

λ> :let matrix = Matrix(2, 2, [1, 2, 3, 4])

matrix = Matrix(2, 2, [1, 2, 3, 4])

λ> :eval det(matrix)

✅ -2

:let vs :define:

| Command | Creates | Persistence | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

:let x = expr | Value binding | REPL session | Store computed values |

:define f(x) = expr | Function | REPL session | Define reusable functions |

The it Magic Variable

After each :eval, the result is stored in it for quick chaining:

λ> :eval 2 + 3

✅ 5

λ> :eval it * 2

✅ 10

λ> :eval it + 1

✅ 11

This is inspired by GHCi and OCaml REPLs. Use :env to see all bindings including it:

λ> :env

📌 Value bindings:

x = 5

📍 Last result (it):

it = 11

📋 Defined functions:

double (x) = ...

REPL Commands

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

:help | Show all commands |

:load <file> | Load a .kleis file |

:env | Show defined functions and bindings |

:eval <expr> | Concrete evaluation (computes actual values) |

:let x = <expr> | Bind value to variable (persists in session) |

:define f(x) = <expr> | Define a function |

:verify <expr> | Verify with Z3 (is it always true?) |

:sat <expr> | Check satisfiability (does a solution exist?) |

:type <expr> | Show inferred type |

:ast <expr> | Show parsed AST |

:symbols | Unicode math symbols palette |

:syntax | Complete syntax reference |

:examples | Show example expressions |

:quit | Exit REPL |

Tip: Use

itin any expression to refer to the last:evalresult.

Multi-line Input

For complex expressions, end lines with \ or use block mode:

λ> :verify ∀(a : R, b : R). \

(a + b) * (a - b) = a * a - b * b

✅ Valid

Or use :{ ... :} for blocks:

λ> :{

:verify ∀(x : R, y : R, z : R).

(x + y) + z = x + (y + z)

:}

✅ Valid

Example Session

λ> :load examples/authorization/zanzibar.kleis

✅ Loaded: 1 files, 13 functions, 0 structures, 0 data types, 0 type aliases

λ> :env

📋 Defined functions:

can_share (perm) = ...

can_edit (perm) = ...

can_delete (perm) = ...

effective_permission (direct, group) = ...

inherited_permission (child_perm, parent_perm) = ...

can_comment (perm) = ...

is_allowed (perm, action) = ...

doc_access (doc_perm, folder_perm, action) = ...

has_at_least (user_perm, required_perm) = ...

can_read (perm) = ...

multi_group_permission (perm1, perm2, perm3) = ...

can_grant (granter_perm, grantee_perm) = ...

can_transfer_ownership (perm) = ...

λ> :verify ∀(x : ℝ). x * x ≥ 0

✅ Valid

λ> :quit

Goodbye! 👋

Tips

- Press Ctrl+C to cancel input

- Press Ctrl+D or type

:quitto exit - Use

:symbolsto copy-paste Unicode math symbols - Use

:help <topic>for detailed help (e.g.,:help quantifiers)

What’s Next?

For a richer interactive experience with plots and visualizations:

Or explore practical applications:

Jupyter Notebook

Kleis provides Jupyter kernel support, allowing you to write and execute Kleis code in Jupyter notebooks. This is ideal for:

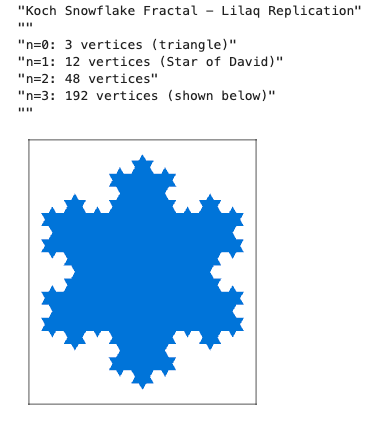

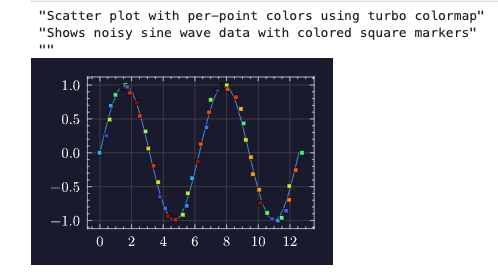

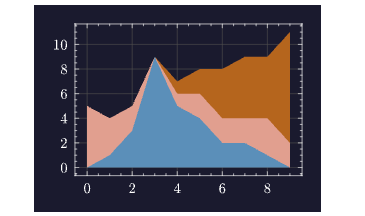

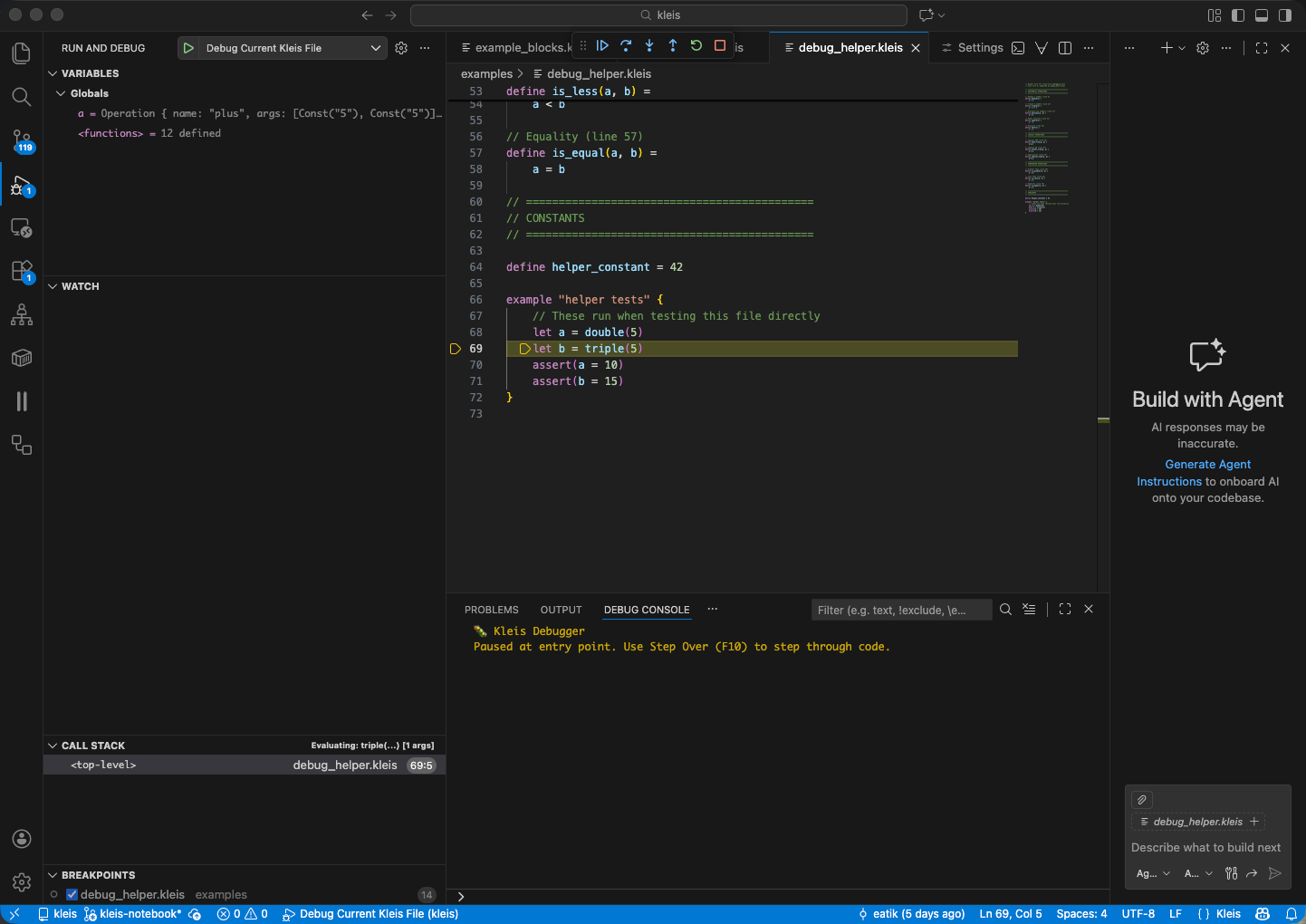

JupyterLab launcher with Kleis and Kleis Numeric kernels

- Interactive exploration of mathematical concepts

- Teaching mathematical foundations

- Documenting proofs and derivations

- Numerical computation with LAPACK operations

- Publication-quality plotting with Lilaq/Typst integration

Quick Start

cd kleis-notebook

./start-jupyter.sh

This will:

- Create a Python virtual environment (if needed)

- Install JupyterLab and the Kleis kernel

- Launch JupyterLab in your browser

Installation

Prerequisites

- Python 3.8+ with pip

- Kleis binary compiled with numerical features:

cd /path/to/kleis

export Z3_SYS_Z3_HEADER=/opt/homebrew/opt/z3/include/z3.h # macOS Apple Silicon

cargo install --path . --features numerical

Note: The

--features numericalflag enables LAPACK operations for eigenvalues, SVD, matrix inversion, and more.

Install the Kernel

cd kleis-notebook

# Option 1: Use the launcher script (recommended)

./start-jupyter.sh install

# Option 2: Manual installation

python3 -m venv venv

source venv/bin/activate

pip install -e .

pip install jupyterlab

python -m kleis_kernel.install

python -m kleis_kernel.install_numeric

Using Kleis in Jupyter

Creating a Notebook

- Start JupyterLab:

./start-jupyter.sh - Click New Notebook

- Select Kleis or Kleis Numeric kernel

Example: Defining a Group

structure Group(G) {

operation (*) : G × G → G

element e : G

axiom left_identity: ∀(a : G). e * a = a

axiom right_identity: ∀(a : G). a * e = a

axiom associativity: ∀(a b c : G). (a * b) * c = a * (b * c)

}

Example: Testing Properties

example "group identity" {

assert(e * e = e)

}

Output:

✅ group identity passed

Example: Numerical Computation

eigenvalues([[1.0, 2.0], [3.0, 4.0]])

Output:

[-0.3722813232690143, 5.372281323269014]

REPL Commands

Use REPL commands directly in notebook cells:

| Command | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

:type <expr> | Show inferred type | :type 1 + 2 |